Matt Cleary

IN the first four seasons of Canberra Royals RUFC, the club was without a clubhouse. Home games and training were at Acton Park2 and players would change on the sidelines or turn up wearing boots and all.

After match ‘functions’ were a keg at Brian ‘Brickie’ Baulk’s place. At the end of season 1952, the Royals’ committee went on a fund-raising drive to build a home. The target sum was 400 pounds – about $17,000 in 2024 money – and members were given a book of tickets worth one pound which was used to raffle a carton of beer and half a lamb. Canberra in the mid-50s was effectively Ainslie and Turner in the north, Yarralumla and Griffith to the south, the dividing line being the Molonglo River. There was a War Memorial, National Library and Lodge. Tuggeranong was snake country. The whole town was the bush, really.

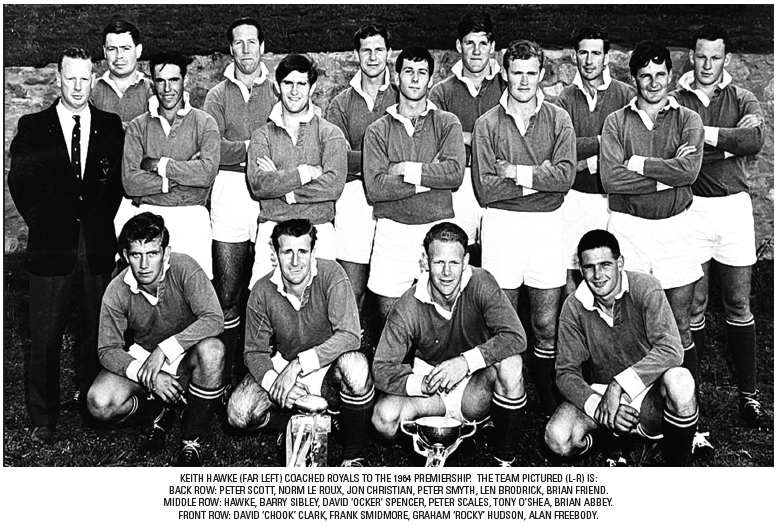

“Canberra was a small country town, maybe 40,000,” Frank Smidmore says in Royals’ 70th anniversary video. “You could’ve called it ‘Fun City’, ‘The City that Never Slept’ … but I don’t think so.” “There were no licensed clubs in Canberra,” Phil ‘Flip’ Meere adds. “So unless you knew a publican very well, it was the Albert Hall or a keg at someone’s place.”

One day, entertainment was found in Goulburn, of all places, where Fred ‘Choppers’ Bloomfield amazed onlookers in a local restaurant. Bloomfield had joined Royals from Manly and quickly became a popular member of the club.

A utility player at home throughout the forward pack, Bloomfield represented NSW Country, ACT and Southern Zone. He was also Royals’ secretary and treasurer in later years. And he was known as ‘Choppers’ because he could eat for Australia.

Before a match in Goulburn, Bloomfield visited a local cafe and polished off a famous mixed grill. He followed that up with a plate full of sausages. He then went on to the rugby field where, according to onlookers, he played as he always did, like a champion.

Queen Elizabeth II came to Canberra in 1954 on the first visit by a reigning monarch to Australia and opened the new session of Parliament in the big white house. The visit was the enema Canberra needed. The stiff-shirts and beardies who showed Her Majesty around were reportedly embarrassed that Australia’s capital city looked like so much grazing land and scrub, with a few nice streets leading to Parliament House. And they set about instructing public servants to get on with the creation of the city that architect Walter Griffin had envisioned.

With a modest 13,000 residents at the end of the war, there was greater development of Australia in the 1950s than in the previous 80-odd years. And much of that growth was in Canberra. The population doubled, construction boomed, and opportunity loomed. And a fresh-born local rugby club decided, ‘we will have some of that’.

Royals’ committee learned that there were hundreds of wooden huts at the Fairbairn RAAF base that the Commonwealth planned to offer tenders for. Jack Waters and Bill Hanley approached the bureaucrats: give us four, and we’ll give you forty quid. They were advised to join the queue like everyone else. Given those beer and meat raffles never did flood Royals with gold, the committee applied for just two of the four-square metre huts. And on April 6, 1955, success! The club was advised that it was the proud owner of huts 228 and 294, and that once they’d written a cheque to the Commonwealth for 20 pounds (about $760 today), they could come and get them.

Though the wooden huts were relatively cheap, the bricks upon which they would have to sit were more expensive, and scarce. In Royals 40th Anniversary Commemorative Booklet it is speculated, though not corroborated, that there was a connection between Waters living opposite a building site in Ainslie destined to be government flats, Waters owning a particularly practical Standard Vanguard station wagon, and the magical appearance of bricks at the Acton site. Records also show an order for 400 bricks and a cheque for six pounds made out to the Canberra Brickworks at Yarralumla. The club, it is safe to say, was not short of bricks. They also had a good man to lay them. Brian Thomas ‘Brickie’ Baulk was first grade’s Best Forward in 1950 and, as a bricklayer, was nominated as site foreman.

And, with help from fellow foundation men, Tom Douch and Les Sutton, both qualified tradesmen, and as many volunteers as they could wrangle with the promise of a fresh-tapped keg afterwards, foundations were laid. Brickie Baulk, according to Keith Hawke, “was a man noted for his sartorial splendour”, enjoyment of Resch’s Pilsener and unconventional workplace health and safety standards.“He always laid bricks wearing slippers. A prop forward, Brickie was very fond of the amber fluid and sometimes – no, often – overdid its intake, which impacted considerably later in the night on the state of his fine clothes,” Hawke said.

The bricks, however, continued to roll in. And foundations continued to grow. Then, along with all those mystery bricks, a mystery hut! A third wooden dwelling – the origin of which remains shrouded in time- appeared on the Acton Flats site to join the two bought from the government. Like a swagman not about to look a stray jumbuck in the mouth, Brickie Baulk and his crew promptly decided that the three huts should become one and joined them in a ‘T’ shape. Inside, they installed flooring and walls, while the roof was made of malthoid, a tar paper impregnated with bitumen. And up she went.

And with the due ceremony of Her Majesty launching The Lusitania, Royals’ first clubhouse was duly christened with several dozen bottles of Reschs Pilsener. It had no showers or electricity and was warmed with kerosene heaters. It was used mainly as training and match-day dressing rooms though on Saturday nights refreshments were supplied through club acquaintances in the local Armed Services Mess. The kegs of beer were picked up and transported back to base by Hawke in his trusty old Ford ute, with Phil Meere, a slashing winger and outside-centre, riding shotgun “to ensure delivery, and that the quality and quantity of the product was maintained,” as chronicled by Hawke inHalf Century of Rugby Excellence. On Sundays, given the need to relieve soreness from Saturday’s games, Royals players used the clubhouse to enjoy further rehabilitation by way of cleansing ales.

Sundays became particularly popular given public consumption of alcohol on The Sabbath was frowned upon, such were the cultural and religious sensibilities of the time. Regardless, the players loved the place – and would do anything to protect it.

Though the clubhouse was sited in a higher and drier area of the Molonglo River flood plain, the greater Acton Flats was subject to regular flooding, and there was often speculation as to whether Royals’ clubhouse would survive a Great Flood. And though the site had rarely, if ever, suffered more than a few centimetres of water lapping against its foundations, a flood alert on radio station 2CA saw dozens of Royals players head urgently for Acton Flats, ‘wading out’ armed with boxes of Resch’s longnecks to ‘save’ the clubhouse. The prompt and selfless action saw the clubhouse become known as ‘The Boathouse’. “We used to have some bloody fun in the floods,” Bob Brown says with a grin. “We’d put a keg on; all your mates.”

This excerpt is from the newly released ‘Blue Bloods: A 75 Year History of Canberra Royals Rugby Union Football Club’ by Matt Cleary.

Click here to buy secure your copy of this limited edition book.